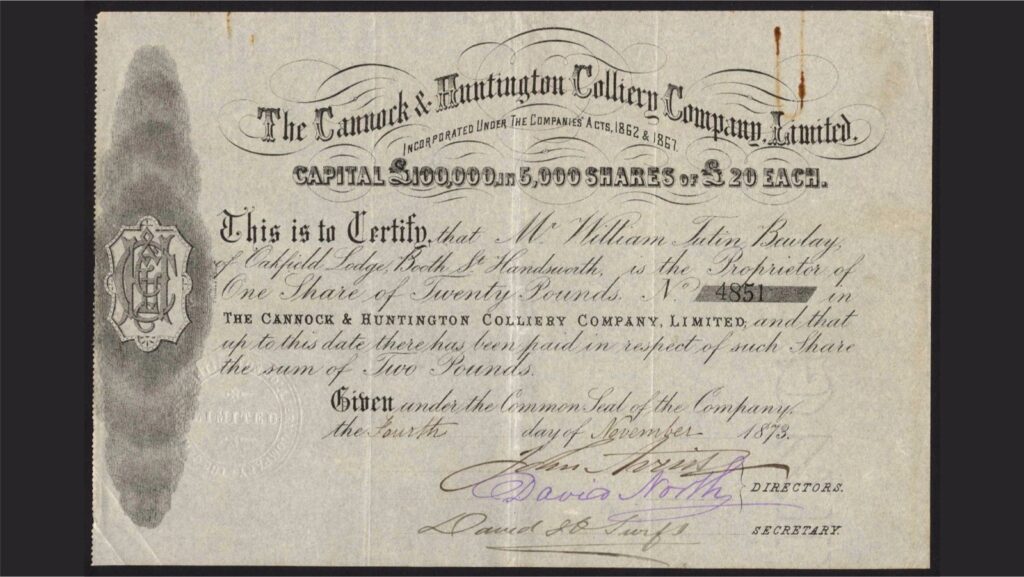

“There is currently no good way to scrap paper shares while maintaining the rights of individual investors,” reads the intro to an opinion column by Financial Times writer Helen Thomas. She supports a recent political initiative for the UK to go bold on reducing the still-strong reliance on paper certificates – despite a list of challenges that would have to be faced.

A Nordic onlooker may find the British debate alien. With the Nordics’ tradition of CSD accounts segregated per individual owner (and a current industry debate that’s instead about how to grow support for more continental “omnibus” account structures which custodians appear to prefer), the UK debate could seem to be going in the absolute opposite direction. Plus … who has actually seen a paper-certificate share since like the 1980s?

Back in the UK, however, Helen Thomas’ column spotlights the twin problems of continued reliance of prevalent paper certificates, and the fact that corporations don’t know who own themselves. In hopeful tone, she points to the prospects of a government initiative, listed among December’s “Edinburgh reforms”, to uproot the dependence on paper certificates and to populate the shareholder registers with more granular data about the actual owners behind the nominees.

One in three is “unallocated”

The proposed changes were detailed in July 2022, in this review, led by Mark Austin, a corporate lawyer. (Yes, it is a thick report in total, but the introductory nine-page “letter to the chancellor” is a vigorous read if the topic interests you.)

“His review found that the average FTSE 100 company has a third of its investor base “unallocated” — effectively unidentifiable — according to Refinitiv data. In the benchmark index, 29 companies have more than 40 per cent unallocated,” FT’s Helen Thomas refers.

Further down, in relation to the costs of administering parallel systems for certificates and electronic securities, she reflects that “part of the reason this persists is that there is currently no good way to scrap paper while maintaining the rights of individual shareholders. It is expensive and impractical for retail shareholders to invest through Crest, the UK’s central securities depository. So most hold shares through a nominee account operated by a broker. That muddies identification of ultimate owners and breaks the chain of communication: companies don’t know who their investors are, can’t communicate with them, encourage them to participate in AGMs, or in fundraisings.”

The readers’ comments below her column are highly interesting, too – ranging from insightful reflections to sarcasm, including combinations.