COLUMN – OLAF RANSOME | R & R: resilience and recovery. That things will go wrong is as certain as death and taxes. How well can your organisation recover when something does? “Be prepared” was something preached to us as young scouts. Real world examples of things going wrong at banks in February offer us a chance to check our thinking on what being prepared should mean.

In a series of six column contributions with PostTrade 360° throughout 2024, banking operations veteran Olaf Ransome digs into the topic of operational resilience – to help us understand its meaning under changing rules, and get adequately prepared. Find his articles listed here.

Murphy’s Law: what can go wrong will go wrong. Of course, s@@t happens. We know that. We also need to be willing to examine what went wrong; were we prepared, can we work out whether and how we can avoid the same thing happening again? Two of my local banks here in Switzerland suffered bouts of Murphy’s this last month. We can learn from those events.

First, what happened? Two separate banks, two separate, unrelated incidents. ZKB, the Cantonal Bank of Zurich, duplicated all the salary payments for the City of Zurich’s 30,000 employees. And, UBS managed to pay out the annual dividend on Nestle shares two months early and before the AGM (Annual General Meeting) had approved it.

Let’s start with the City of Zurich. First, I need to get over the staggering number of city employees. One for about every 13 residents. New York City has about one for about every 21 residents. Maybe not a like for like comparison. In any case, my views on government efficiency or lack thereof are for another time and place.

What happened? Apparently, the duplicated payments were down to a software failure at ZKB. That failure was in a system operated by an outsourced provider, Swisscom, who in turn had contracted development out to another firm. So far, we are told, the error was down to a software bug.

We should think of resilience as being two things: stopping things going wrong and then being able to recover.

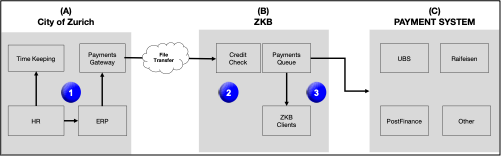

The graphic shows my view of how these things probably work. The City of Zurich’s systems (1) did the right thing and sent the payments file to ZKB. There was enough money (2) and payments were made (3). Then the bug in ZKB’s system caused the same batch file to be loaded up a second time. There was either enough money in the account or a credit line, so the payments were not stopped and off they went, again.

In looking at resilience, we should think of resilience as being two things: stopping things going wrong and then being able to recover. Stopping duplication; is that possible and realistic? Payroll processing is different from you and I entering a payment on an app or browser. I know that Raiffeisen where I have my company’s accounts will warn me if I enter two payments to the same recipient. Here we have a batch. I would say that payroll is the single biggest regular expense each month. Maybe more goes out if some borrowing is being repaid. So, I’d expect there would be at least a four-eyes check inside ZKB on that batch file and I’d expect there is a relationship manager keeping an eye out that payroll was processed as it should be. You do not want to be responsible for that going wrong. Then I’d say that any payment above say 1 million francs is not normal. We can debate that threshold, but any batch for 175 million Swiss francs is not normal. So if there was a four-eyes check, somebody was asleep; adequate procedure not followed. If the batch was processed twice without a four-eyes check, then we have an inadequate procedure.

The other side of this is recovery. If it goes wrong, can you recover easily? This is where things get tricky. It would be easy enough to recover the money from any City employees who bank with ZKB. But, once payment is made externally, that door is closed. You can’t pull the money; the employees have to push it. Here in Switzerland, the latest version of how private clients make payments is QR-code centric. For example, mobile carrier Swisscom sends me an invoice with a QR-code. I scan it and make payment, with the specific reference coming from the QR-code and then Swisscom know that payment was from me, even if there were others paying the same amount.

So, how do you get the QR-codes to those 30,000 folks and get the money back as soon as possible? E-mail maybe. It seems the City of Zurich does not know if all its employees have e-mail and a computer. Maybe some do not even have a City of Zurich e-mail address. So, our wonderful, overstaffed City sent letters by post to all 30,000 employees. Yes, ZKB is going to pay for the costs of the mess, but we the taxpayers own that too. I’d bet money that close to 100% of all of those 30,000 have private e-mail and already receive bills with QR codes in their everyday life. A switched-on HR department would have ensured they have private e-mail addresses, private mobile numbers, and a waiver for sending personal information by e-mail. Just maybe there is some reason that a handful of those 30,000 didn’t have a personal e-mail, but I’ll bet you they all have a mobile phone.

A switched-on HR department would have ensured they have private e-mail addresses.

Your institution is different. And you may argue with me about whether an employer should send things to employees via e-mail. Fine. The point here is that if you think through what can go wrong and what you need, you set yourself up for when Murphy’s Law hits you. And you might just stop sending so much mail by snail mail too.

On to UBS, where clients holding Nestle shares received a dividend payment two months early. First, prevention. As soon as the dividend is announced, UBS and every other financial institution use that data to update their systems. Stocks have things called ex-dates, record-dates, and payment dates. The former is when the stock trades ex dividend, so if ex-date is Apr 10, and the stock closes at CHF 10 on Apr 9, with a CHF 1 dividend to be paid, then the stock is expected to trade at CHF 9 on Apr 10. Record date is when the processing systems determine who holds the stock and who receives the dividend. Nothing should be paid before record date. Payment date is when money is paid. Again, there should be a four-eyes process in place. UBS is a big place and pays a lot of dividends on lots of stocks from all around the world. I doubt they have an inadequate procedure. I’d be checking: “is there any way record date and payment date can be finalised without a four-eyes check by two humans?”. My money is on no and on “adequate procedure not followed”.

Now, this is all about internal processing. In the graphic above, this is only about boxes A & B. UBS can and did reverse the process. Both the unintended credit and the reversal, the debit, showed up in customer accounts. Then the phones start ringing, and the e-mail enquiries arrive. It was absolutely the right thing to do to reverse the entries, but what about the communication to clients? Same kind of problem as ZKB, but a bit more sensitive. There is a small subset of clients at any private bank who really do not want any e-mail or even physical mail from their bank.

Knowing that resilience is a hot topic for regulators, if I was regulating UBS, I’d be asking both about why this happened and how well-prepared UBS is to communicate with its clients.

Your institution is different. Sure. Don’t get hung up on this being a Swiss bank, a Swiss stock, or a dividend, or a payment for a Swiss city. Take a minute and think through: could something similar but not exactly the same as this happen in your shop and how would you communicate with your clients? If I was in your institution I’d ask: “Could that happen here, and how ready are we to respond”.

Referring to himself as The Bankers’ Plumber, Olaf Ransome is founder of 3C Advisory LLC – drawing on decades of senior operational experience from large banks. To connect, find his LinkedIn page here.